A longer piece: Beijing’s All-Out Crackdown on the Anti-Extradition Protests in Hong Kong https://www.prcleader.org/victoria-hui

A shorter piece: Hong Kong’s Protests: Look Beyond Tiananmen 2.0

Excerpts:

In 1989, Hong Kong people marched under the banner “Today’s Tiananmen, Tomorrow’s Hong Kong.” Thirty years later, the Tiananmen incident still has uncomfortable resonances in Hong Kong.

… the most notable similarity with Tiananmen is the fomentation of “riots” to justify a brutal repression.

… Why and how did Hong Kong’s protests go from peaceful rallies to fiercer forms of protest?

… All of Beijing’s previous attempts at undercutting Hong Kong’s freedoms were pushed back by peaceful protests. But because it is difficult to repress peaceful protesters, part of Beijing’s effort has been focused on turning them into violent protesters.

The process of radicalizing peaceful demonstrators has various steps, and the first move by Beijing has often been to refuse to make concessions, thereby forcing the opposition to either abandon their demands or to step up their actions. At Tiananmen Square, students escalated by going on a hunger strike. In Hong Kong, the government’s unresponsiveness to multiple peaceful marches gave rise to the protest slogan: “It is [you] who taught us that peaceful demonstrations are ineffective.”

As if to reinforce this conviction, the authorities have increasingly closed off nonviolent means of expressing dissent.

The Civil Human Rights Front, an organization that has led peaceful marches without incident since 2002, mobilized 1 million people on June 9, 2 million on June 16, and 1.7 million on August 18. However, the police have rarely issued “no-objection notices” after August 18 – rendering many subsequent protests “unlawful assemblies” to be cracked down upon in the eye of the law. Jimmy Sham, the Front’s convener, was even attacked twice by hired thugs.

Protesters have formed human chains, spontaneously sung “Glory to Hong Kong” across the city, and promoted their cause through public art and “Lennon Walls.” These peaceful displays of solidarity, however, are subject to same risks as other “unlawful assemblies”, and much of the art has been destroyed by government agents and counterprotesters. Supporters have been arrested by the police or stabbed by pro-Beijing thugs.

Strikes and boycotts, other popular nonviolent tactics, have also been made ineffective in Hong Kong, with Beijing responding by manipulating businesses across the city to punish employees who participated.

Indeed, the authorities have little tolerance for such nonviolent means of dissent because they are the hallmark of “color revolutions.” As a Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office spokesman said, the goal of general strikes and class boycotts is “to paralyze the Hong Kong government” and “seize the power for governing the Special Administrative Region.” Hong Kong Education Secretary Kevin Yeung issued a warning that students in uniform “should not stage, or participate in political activities, including class boycotts, singing songs, chanting slogans, forming human chains or other related activities like distributing flyers promoting political messages.”

To further tighten the screw on freedom of expression, the government imposed a mask ban on October 5. Most protestors wear masks to both hide their identities and protect themselves from tear gas and pepper spray. The high court ruled the ban unconstitutional on November 18, but Beijing immediately criticized this decision as a usurpation of central authority, never mind the original guarantee of judicial independence for local courts.

In addition to stifling legal and peaceful channels of expression, Beijing has also used brutality to intimidate some potential protesters and provoke violent reactions from others.

On this, we should turn our focus to the “other Tiananmens” across China in 1989. As analyzed by journalist Louisa Lim, for instance, party leaders deployed the police rather than the military in the inland city of Chengdu. The Chengdu police’s goal was not to disperse crowds, but to “annihilate” the movement by beating protesters to death and by ordering hospitals to stop accepting the wounded.

The repression in Hong Kong has echoes of the Chengdu model, short of outright killing. The Hong Kong police have beaten protesters with batons, breaking the bones of those already pinned down in direct view of journalists and passersby. The police fired point blank at a protester who had no weapon in his hands on November 11. Near the besieged Polytechnic University, police vehicles took on a new “battle tactic” to ram at high speed into protesters, causing a stampedeand severe injuries. Parents of students trapped inside were less worried about their children getting arrested per se, but more about their sons and daughters enduring broken limbs, sexual assault, and other forms of torture under arrest.

The police have also arrested first responders, blocked the path of ambulances, and rounded up suspected protesters at hospitals. Doctors and nurses, who know first-hand the extent of bone fractures and brain injuries, have staged sit-ins with the slogan “Hong Kong police attempt to murder Hong Kong citizens.” International observers complain that police operations are “unheard of in civilized societies” and have systematically violated international humanitarian norms.

Another aspect of the Chengdu model is the use of provocateurs and criminals to set fires to the People’s Market to discredit the movement and provide justification for an all-out repression. In Hong Kong, there is reasonable suspicion that some of the large-scale destruction was committed by officers dressed as protesters, who were escorted away rather than arrested by uniformed police.

The Hong Kong police have allegedly colluded with gangsters to beat up protesters, organizers, and journalists alike. The indiscriminate assaults by thugs in Yuen Long on July 21 and after triggered vigilante justice.

Driven by both the closing of legal dissent and the intensity of regime brutality, protesters have increasingly turned to violent escalation. This has, in turn, opened up the opportunity for agent provocateurs to further inflame the “riots.” As images of black-clad people emerge from vandalized shops and train stations, it is difficult to sort out who is a protester and who is in disguise.

Just as the narrative of smashing and burning helped to justify a heavy crackdown in 1989, Hong Kong protesters’ turn to firebombs has given credence to the authorities’ call to “stop the violence and end the turmoil.”

The sieges of university campuses represented a major escalation to wipe out the most determined young protesters under the new police commissioner Chris Tang. The police arrested 1,377 “rioters” from and near the Polytechnic University alone, taking the total number of arrests to 5,890. Mass arrests of protesters not just from the streets but also residential buildings, universities, and secondary schools means that there is no refuge for what Chief Executive Carrie Lam calls “enemies of the people.”

By manufacturing the “riots,” Beijing has managed to not just inflict debilitating injuries on rebellious youth, but also take down Hong Kong’s pillars of freedom. It has stifled freedom of assembly and undermined local courts’ final jurisdiction. These measures would have been unthinkable in Hong Kong’s more peaceful times.

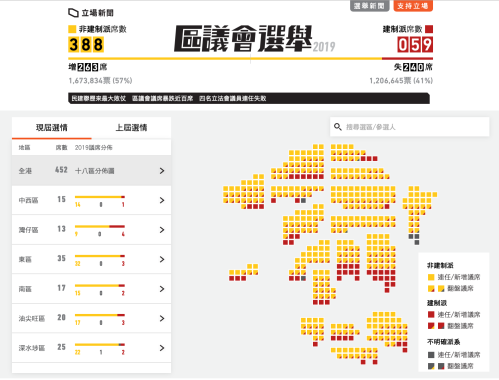

… if a “Tiananmen 2.0” has been averted, this has to do not just with domestic events, but also with the city’s international status and international support. In 1989, international sanctions against Beijing came only after a bloody massacre. In 2019, the U.S. Congress tabled, debated, and passed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act in the face of heightening police brutality. It may not be sheer coincidence that the Chief Executive Carrie Lam agreed to suspend the extradition bill on June 15 after Senator Marco Rubio re-tabled the Act on June 13, that she announced the withdrawal of the bill on September 4 when the Congress held a hearing on U.S.-China relations, and that the District Council election was not delayed or canceled when the Act was set to pass.

For these reasons and more, the “Tiananmen 2.0” analogy has turned out to be overblown. And this is not because Beijing has “acted responsibly” as U.S. President Donald Trump said, but because the U.S. Congress and the rest of the world have kept a close watch.

See the entire piece at https://thediplomat.com/2019/12/hong-kongs-protests-look-beyond-tiananmen-2-0/

New York Times photo: Protest photo evokes memories of Tiananmen era