US-China Economic and Security Review Commission

Hearing on “U.S.-China Relations in 2019: A Year in Review”

Wednesday, September 4, 2019

The event and the written testimony: https://www.uscc.gov/Hearings/us-china-relations-2019-year-review

The video: https://www.c-span.org/video/?463934-2/us-china-economic-security-review-commission-holds-public-hearing-part-2

The oral beginning statement:

The Hong Kong Reckoning

Thanks so much for giving Hong Kong a voice.

I was born in Hong Kong and I grew up in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong protests are both academic and personal to me.

China watchers have raised the phenomenon of “China reckoning” in U.S.-China relations: that Americans have only belatedly waken up to China’s increasingly aggressive trade and security policies.

If international observers had paid more attention to Beijing-Hong Kong relations over the years, a “Hong Kong reckoning” could have led to an earlier “China reckoning.”

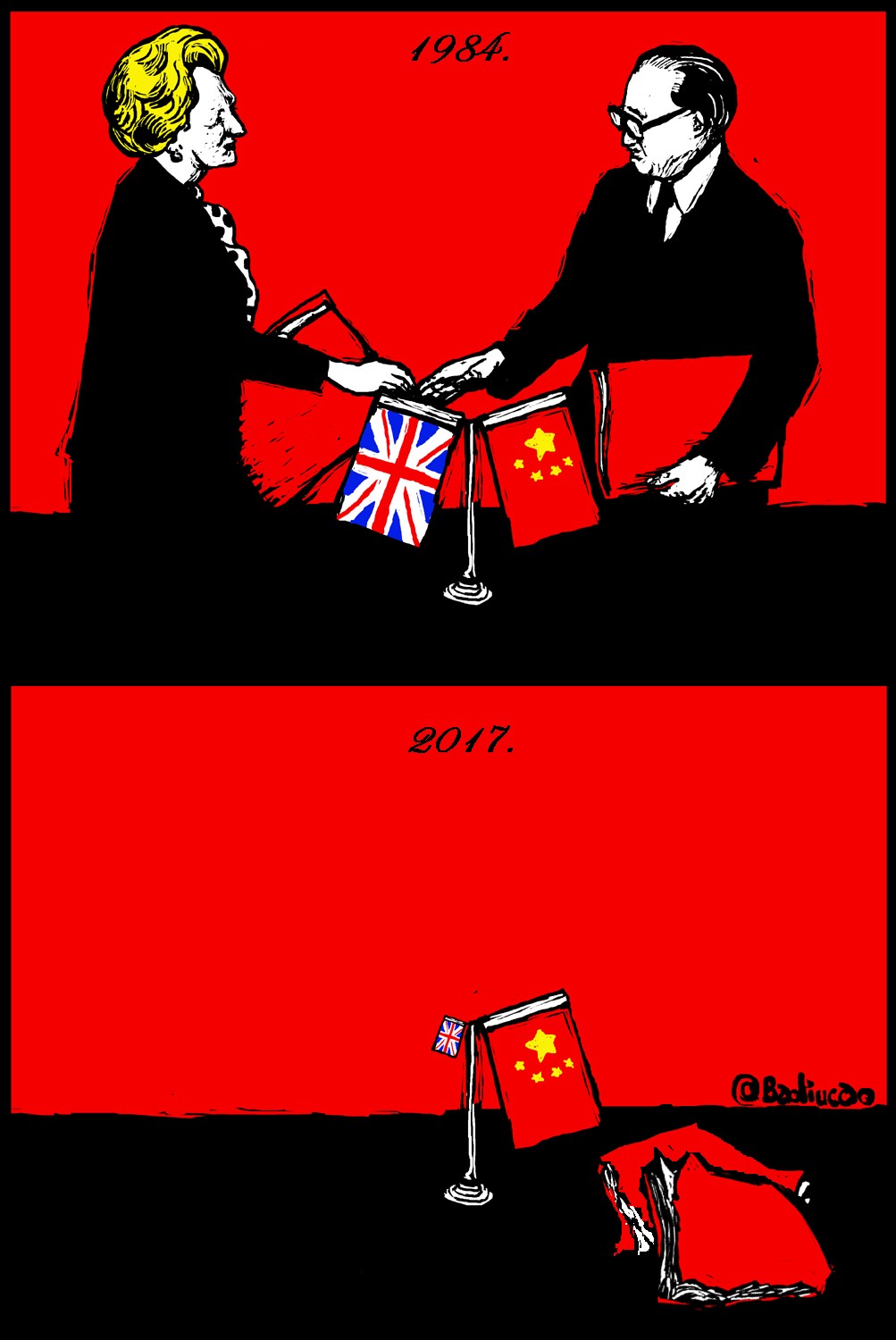

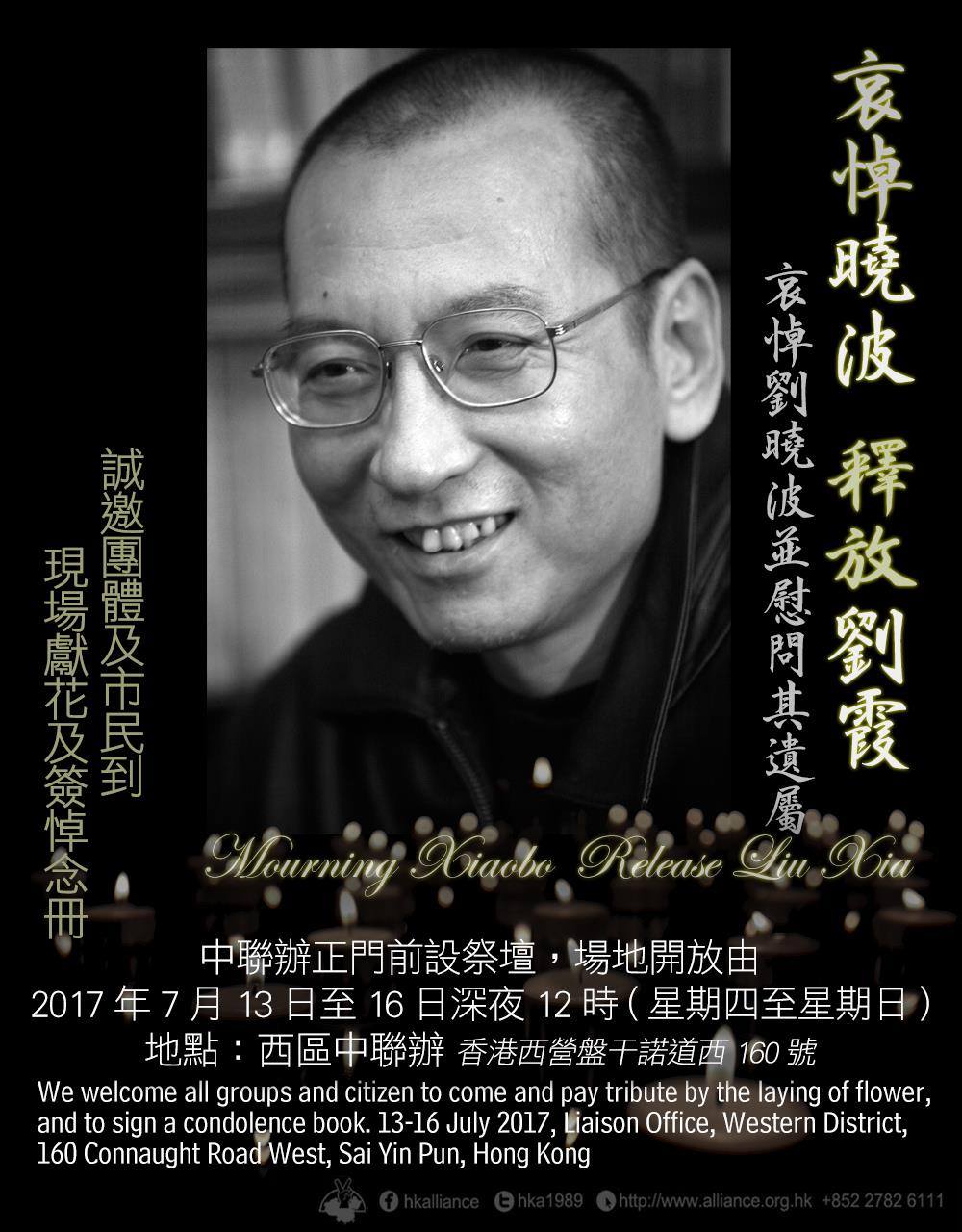

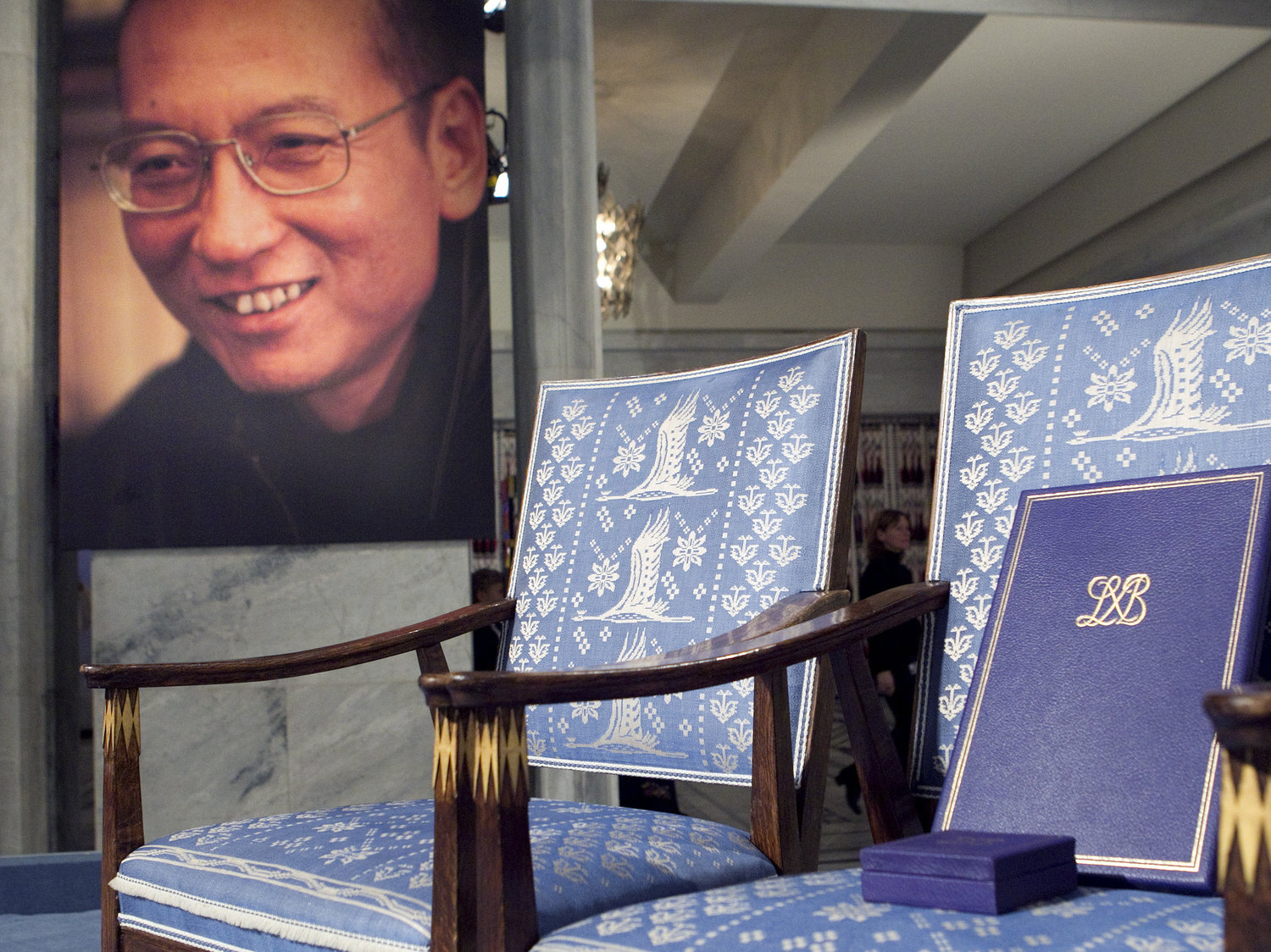

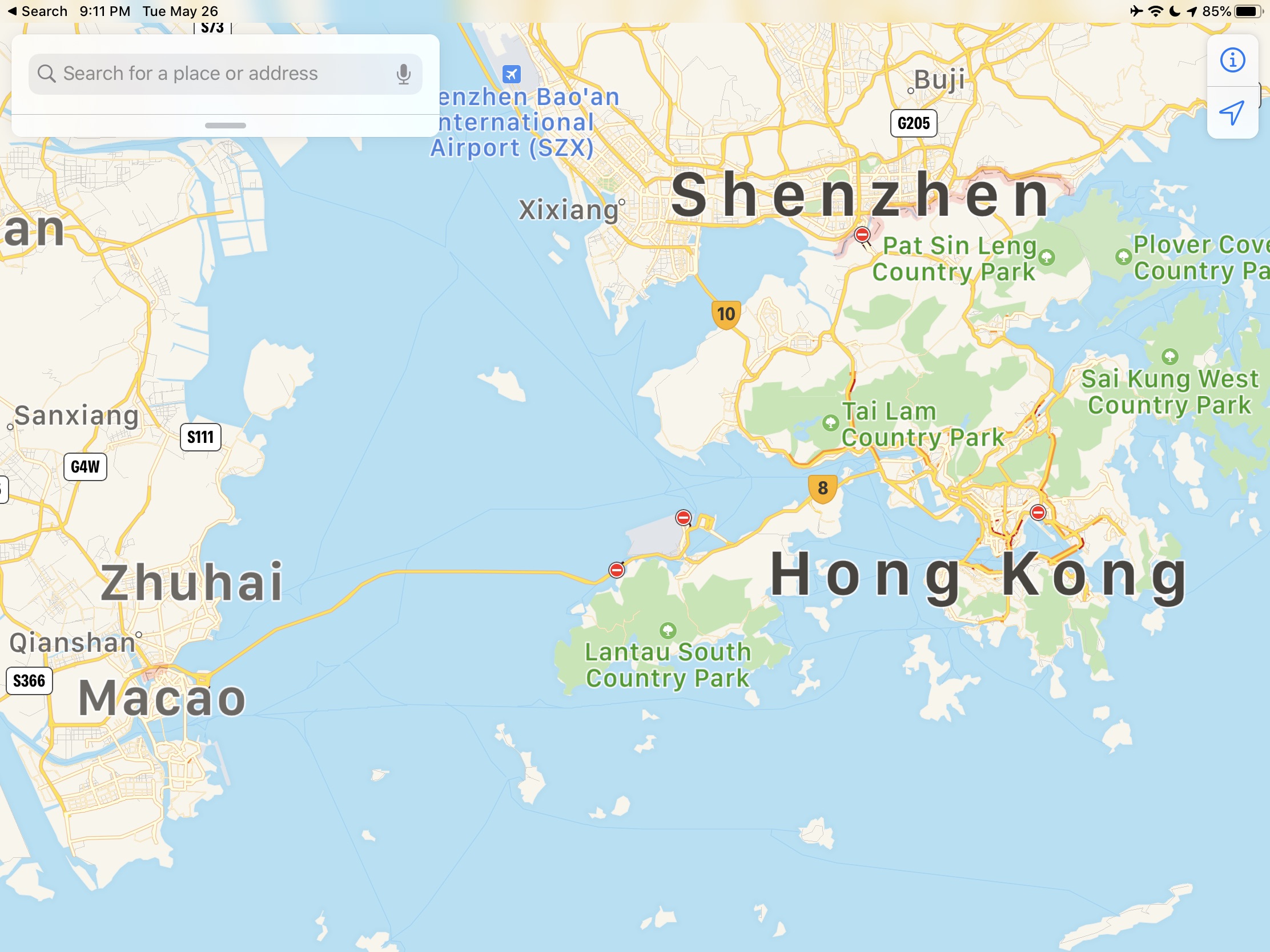

Beijing has broken the promise of “Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong” with a “high degree of autonomy” under the “one country, two systems” model — written in black and white in the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Hong Kong Basic Law.

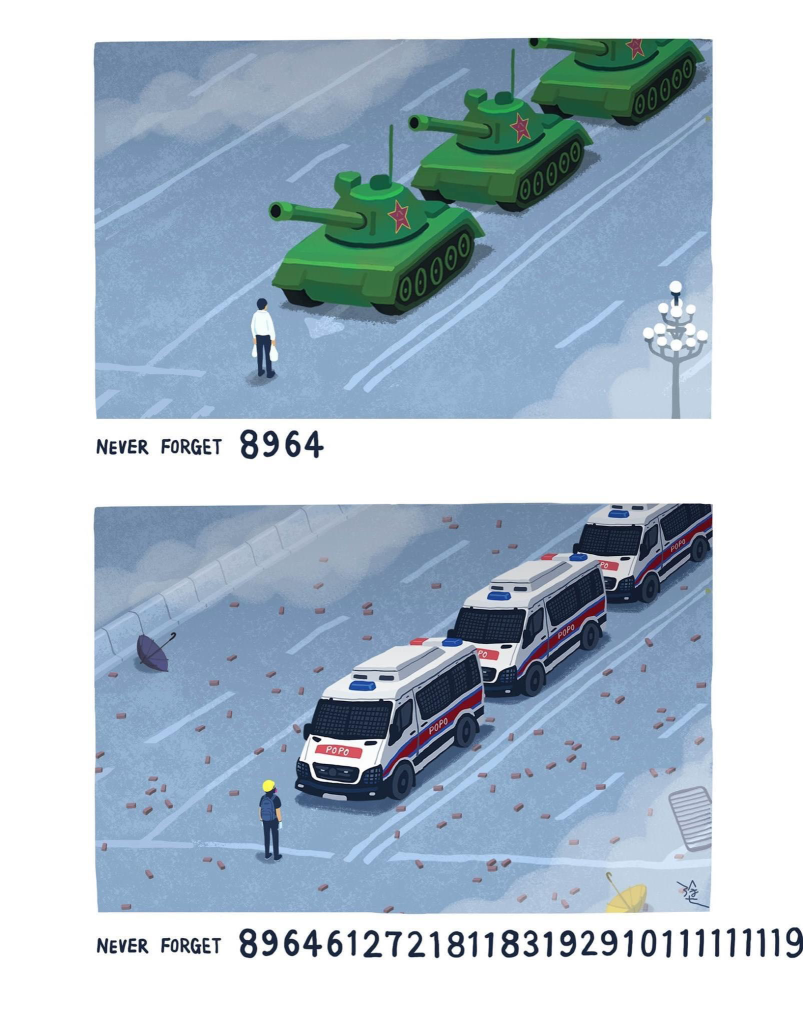

Many people believe that all is well in Hong Kong so long as Beijing does not roll out tanks into the streets of Hong Kong in Tiananmen-like fashion.

My friend Victor Shih testified this morning that China’s approach to Hong Kong has been “soft” and “moderate.”

It is a mistake to narrowly define “violence” by looking only at PLA deployment.

This view distracts from how Beijing has controlled Hong Kong through nonmilitary but still heavy-handed means.

In order to quell the current protests, Beijing has deployed the Hong Kong police without rolling out Chinese troops, used the Hong Kong government to take draconian measures without formally declaring emergency, and wielded less visible, whole-of-society white terror without creating bad optics.

The U.S. Congress and the U.S. Government should broaden monitoring efforts from Chinese troop deployment to the daily repressive measures already applied in Hong Kong.

The protests started with the call to withdraw the extradition bill, which would have required Hong Kong to turn over accused offenders to mainland China.

The Chief Executive Carrie Lam “suspended” the bill on June 15. But she refused to withdraw it until early this morning.

This concession is too little too late.

In refusing to address protestors’ demands, the Authorities have relied on Hong Kong’s police to repress the escalating protests in the last two and a half months.

This policy has corrupted what used to be Asia’s finestpolice into “just another mainland force.” When I was a little girl, my mom would tell me that, “whenever you get lost, go get help from a police uncle or aunty.” That was the level of trust then. Today, as shown in global TV, the police arbitrarily beat up and arrests Hong Kong people.

It is not even obvious who the police answer to. When the Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung, Carrie Lam’s second in command, apologized about police actions, he was publicly rebuked by the Police Inspectors’ Association.

To make it even clearer that it is Beijing ruling from behind the scene, the central government’s Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office in rare press conferences said: “We should relentlessly crack down on… violent criminal acts without mercy, and we firmly support Hong Kong police and judicial authorities” in doing the job.

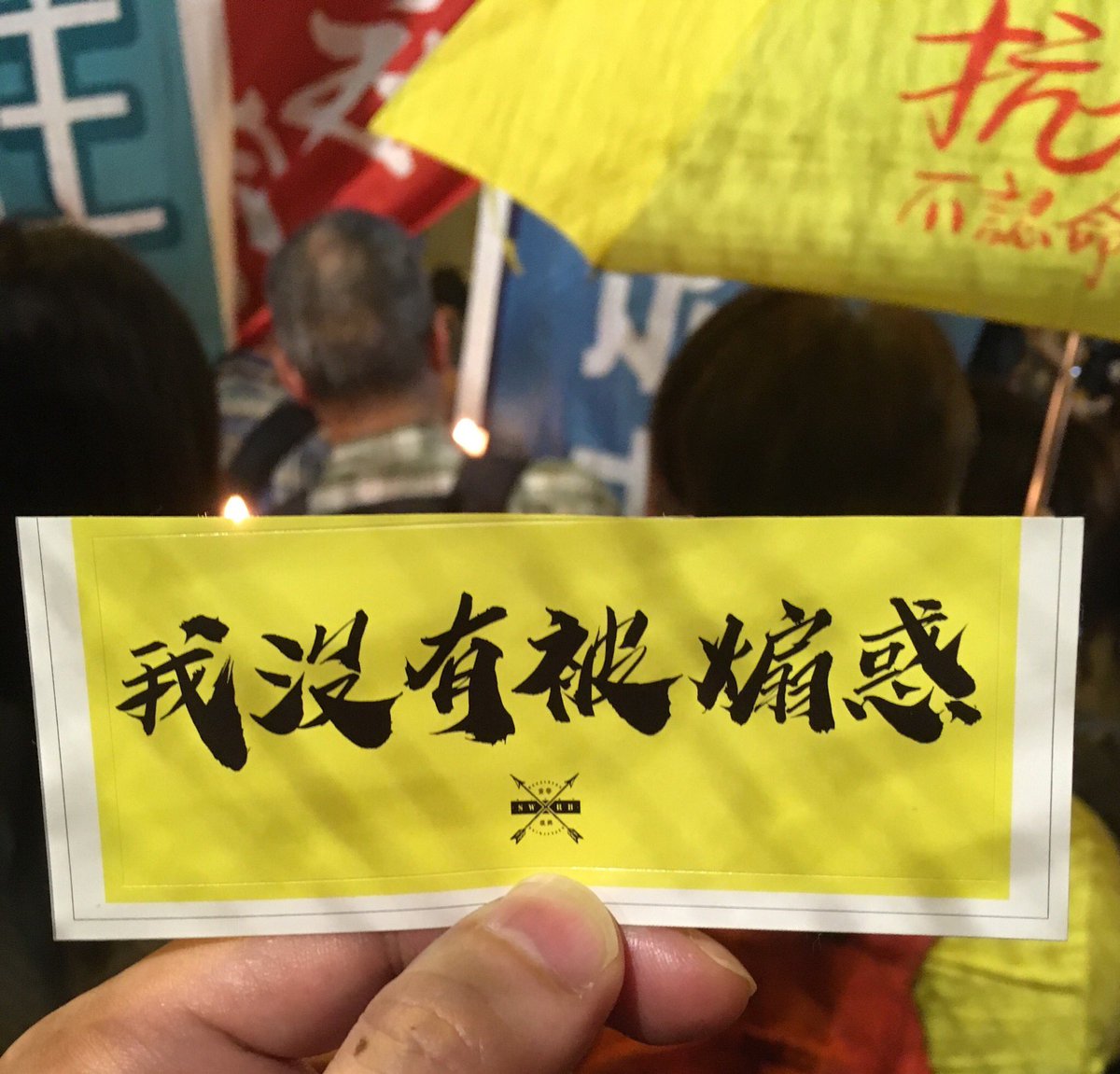

Beijing has additionally stepped up a white terror campaign to silence the larger society.

The written testimony chronicles such repressive measures up to September 2. The rest of my oral testimony will only highlight the key points.

The first point: The bloody crackdown.

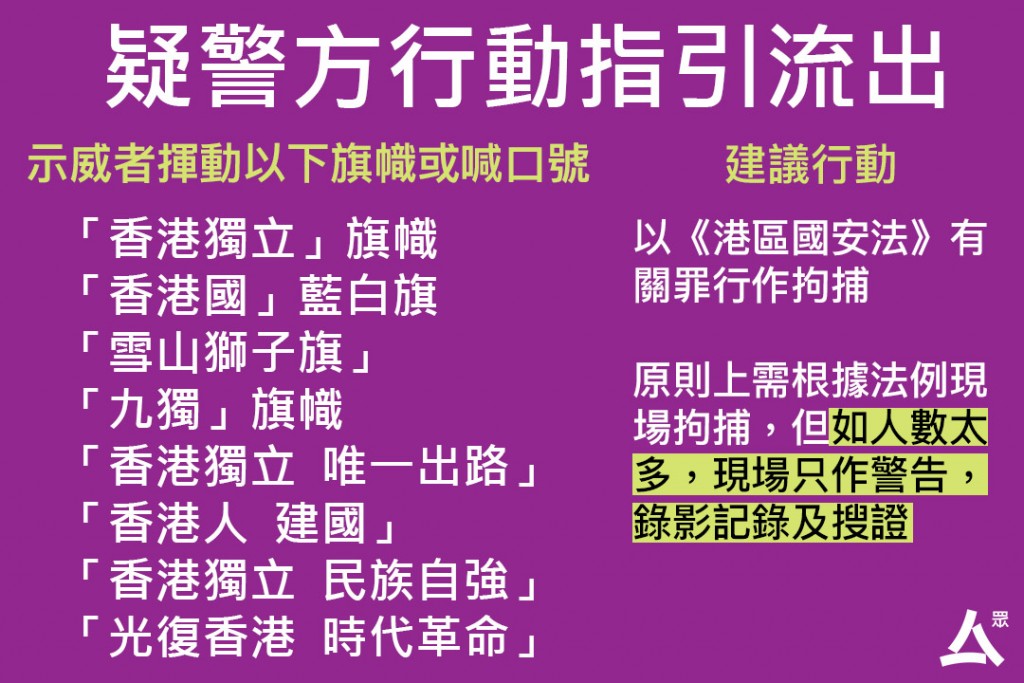

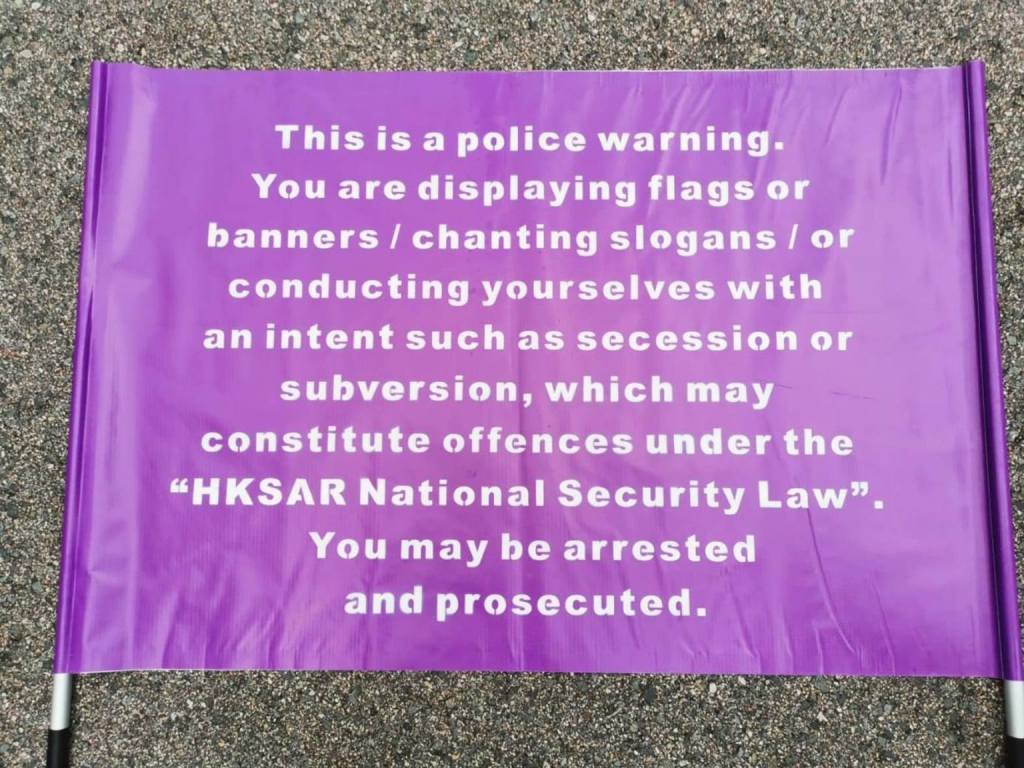

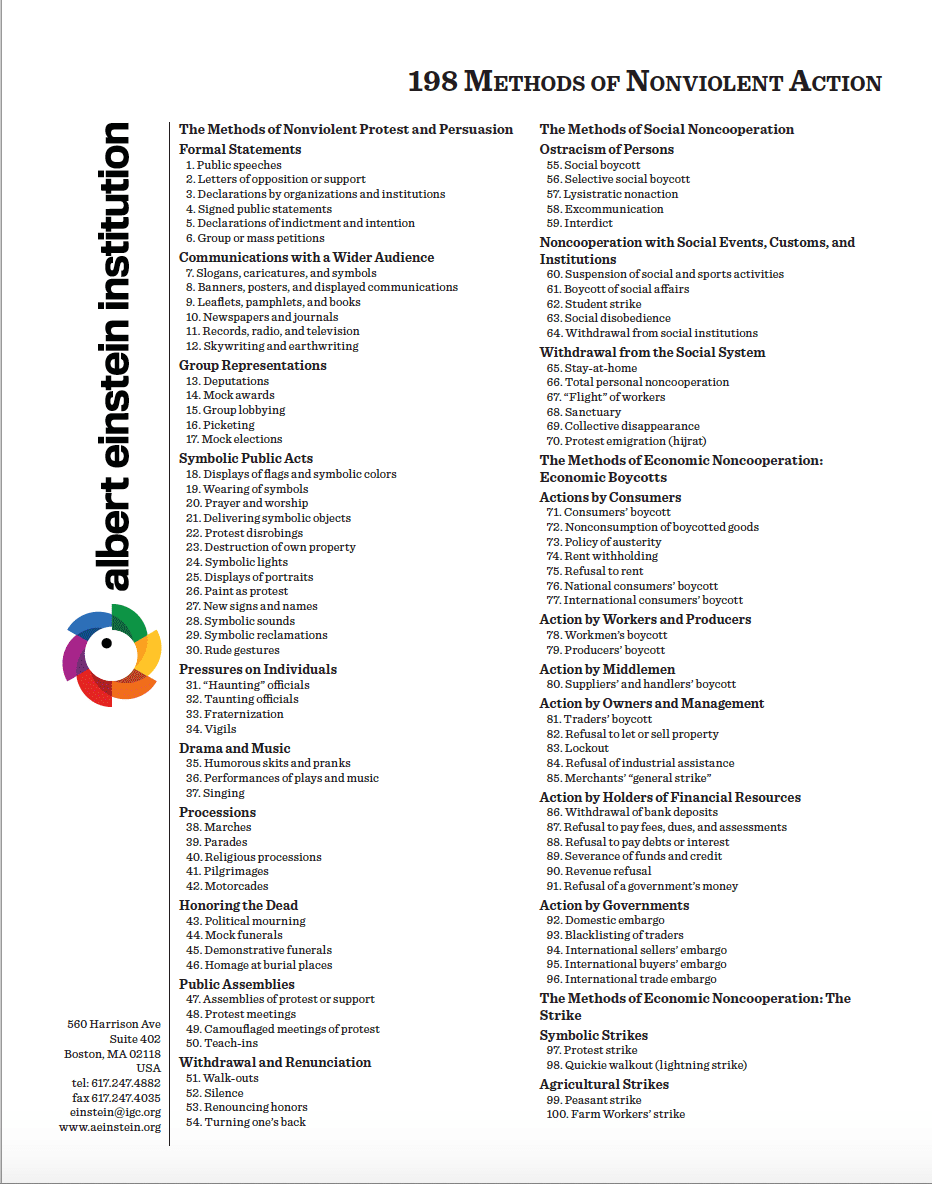

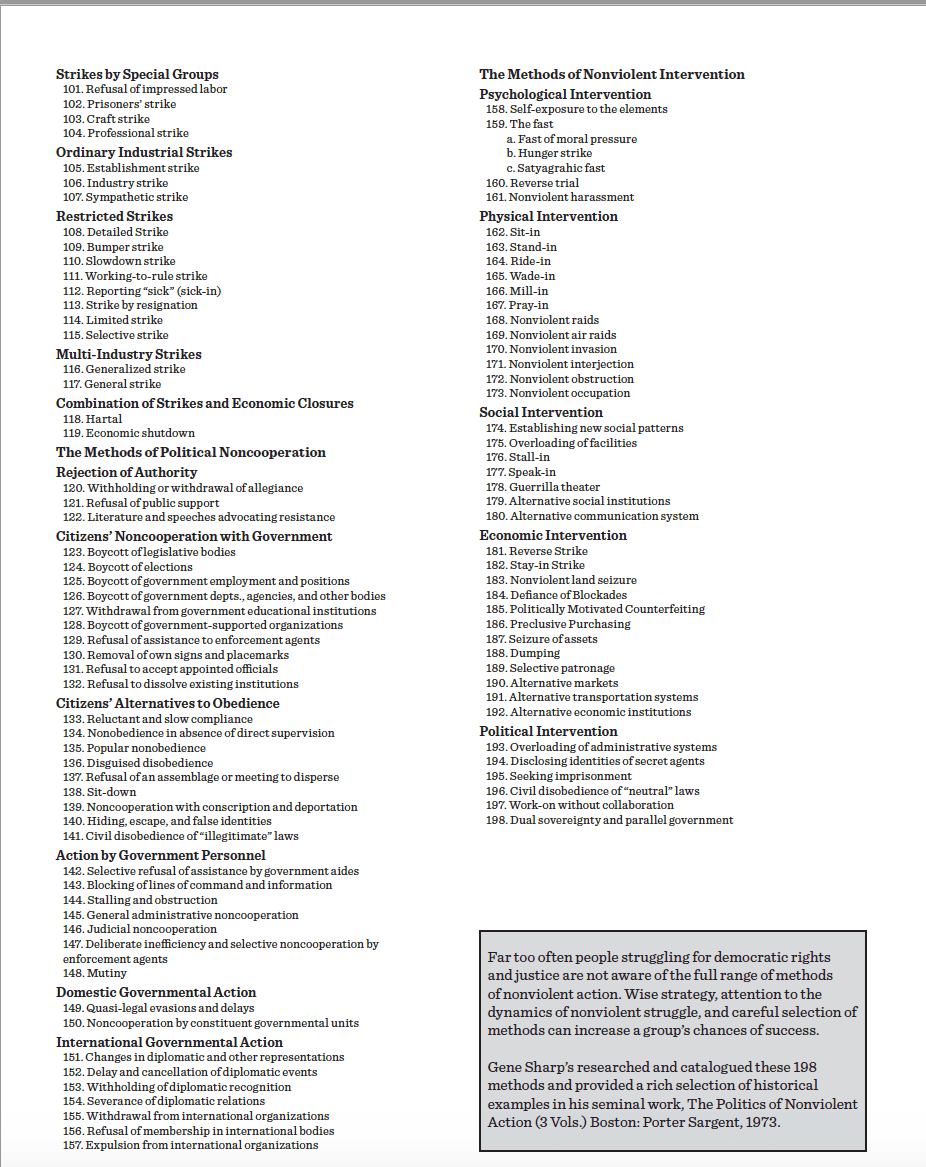

The first tactic in the police toolkit is to restrict the freedom to protest by refusing to issue a “no-objection notice” — essentially, a permit. This technically renders protests “unlawful.”

Second,the police have arrested more than 1,100 peoplesince June, charging many with not just “unlawful assembly,” but also serious crimes such as rioting, assaulting the police and possessing weapons.

Third, the police routinely hit protestors with batons and fire tear gas, pepper spray, beanbags, rubber bullets, and sponge grenades.

The first “bloody Sunday” happened on August 11and more bloody arrests have taken place since.

The UN Human Rights Officeand Amnesty Internationalhave accused the Hong Kong police of using crowd control weapons in waysthat are prohibited by international standards.

What is not visible to reporters and bystanders is even more disturbing. Many of the detained were denied access to lawyers for many hours, and stopped from contacting families. Some of them were so brutally beatenin detention that they came out with broken bones and head injuries.

It is noteworthy that doctors and nurses have repeatedly staged sit-ins with the slogan “Hong Kong policeattempt to murder Hong Kong citizens.” A nurserecounted how one detainee’s wrist is connected only by skin, with bones and tendons both broken in x-ray. Medical workers have also complained about inhumane rules and procedures: that ambulances are not allowed access to the wounded at protest sites without police approval, that the police arrestsuspected protestors at hospitals so that the injured are fearful of seeking medical treatment, and that medical staff are restricted from calling families on patients’ behalf.

Most alarming, police forces are credibly suspected of collusion with criminal gangswho have assaulted both reporters and protesters.

This biased enforcement of the law and complicity with lawless attacks on protestors has turned Hong Kong into a police state, even a mafia state.

The second point: Hong Kong has taken Emergency Measures Without Declaring Emergency Since August 30

The authorities were particularly worried about August 31, the fifth anniversary of a Beijing decision to deny universal suffrage that had sparked the Umbrella Movement of 2014.

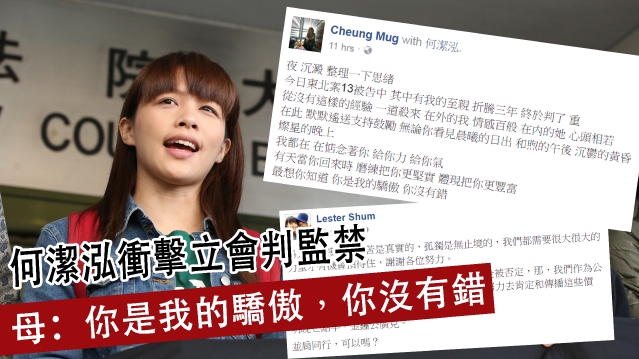

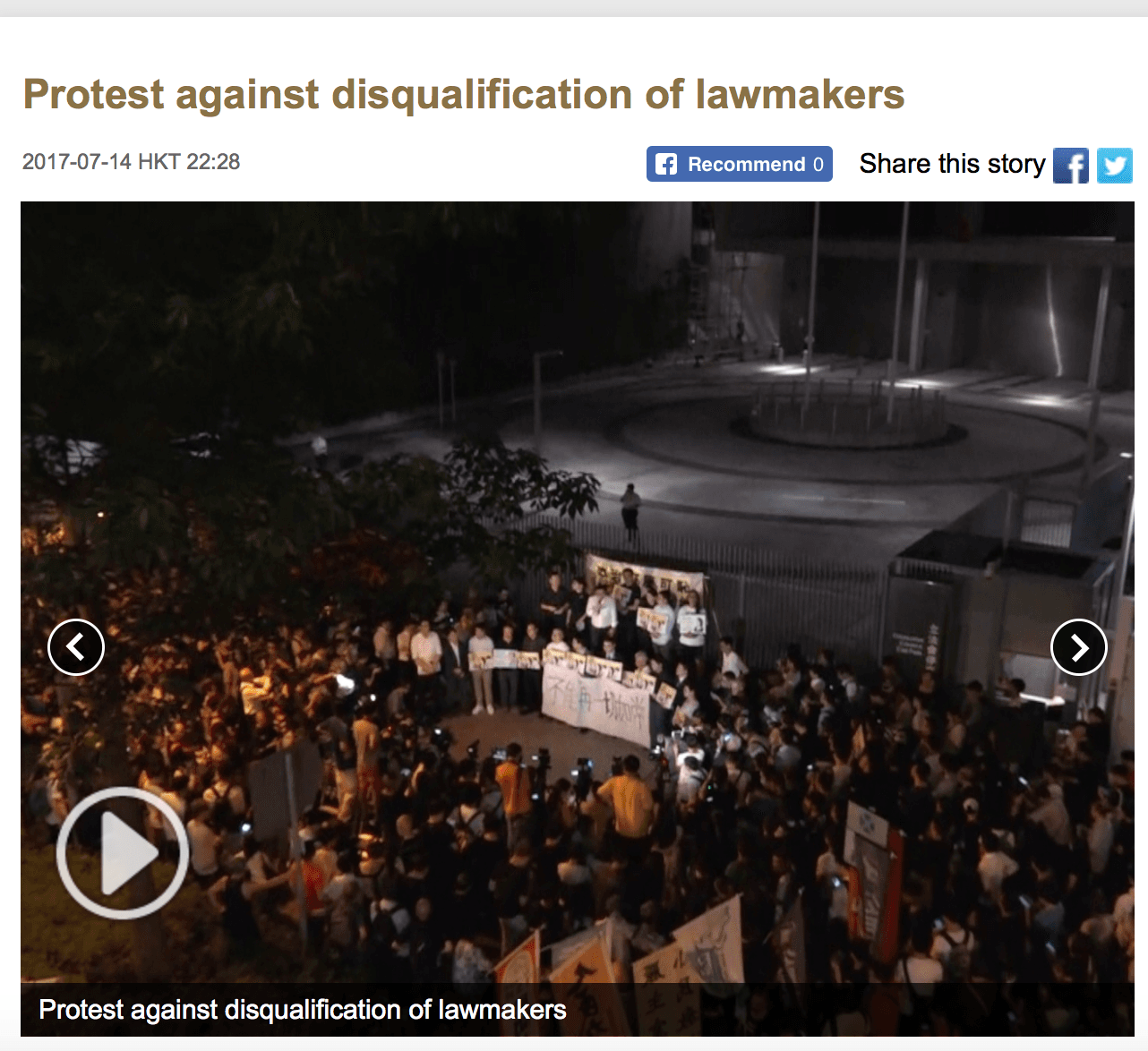

The day before, the police arrested well-known legislators and activists as a preemptive move to suppress protest turnouts the next day.

To further intimidate the public, the police for the first time imposed a total banon a peaceful march organized by the Civil Human Rights Front on August 31.

The police then took severe measures against those who dared to protest.

They deployed water cannons with blue dye for the first time, leading analysts to draw analogy with martial law under theapartheid regimein South Africa.

The police also stormed into the Prince Edward metro station with batons and pepper spray. The early horrifying scenes were caught on live streamsand videos. The police later ordered reporters to leavethe station. Medical staff were also notallowed in for 2.5 hours. The police acted more violently that night than the notorious gangsters has before.

Pro-government voices have been advocating the imposition of emergency to put an end to the escalating protests. However, if the Hong Kong police are already taking away citizens’ right to protest arbitrarily arresting democratically elected law-makers and activists indiscriminately beating up passengers inside train stations banning reporters from covering police abuses denying medical workers access to the wounded arresting social workers who mediate between the police and protestors breaking the bones of the arrested, then the Hong Kong government has effectively adopted emergency measures even if it has not formally declared emergency.

The third point is a widening white terror to punishprofessionals.

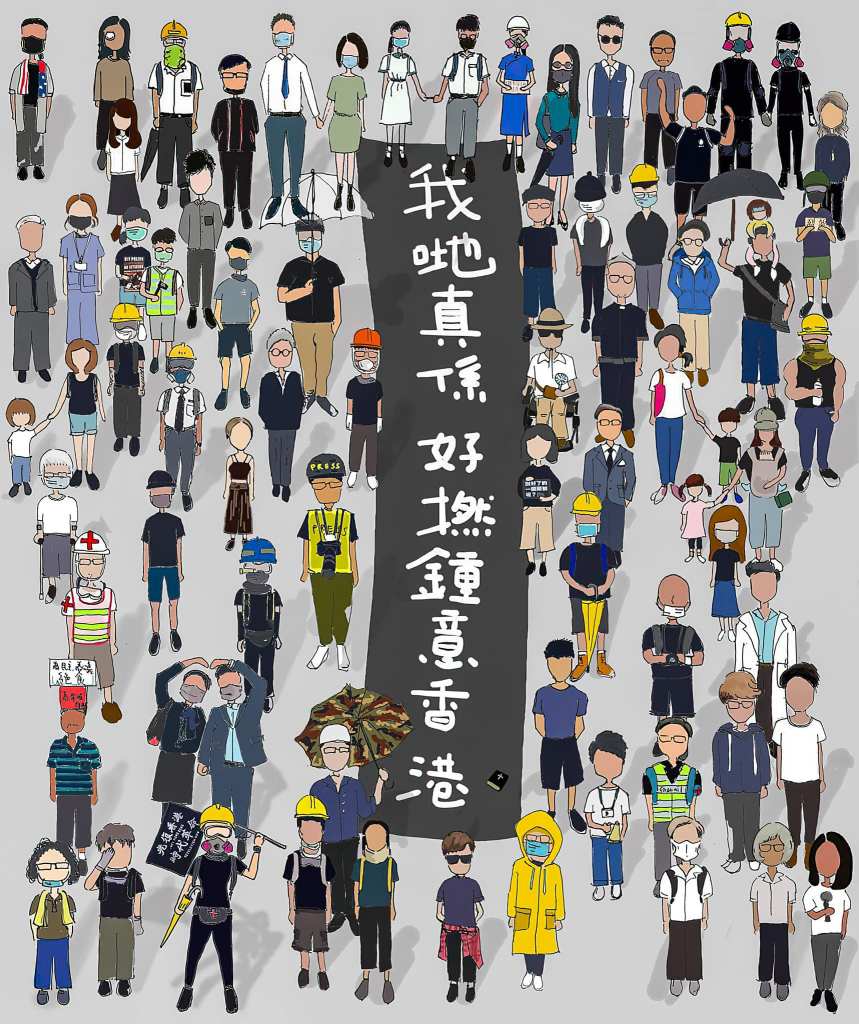

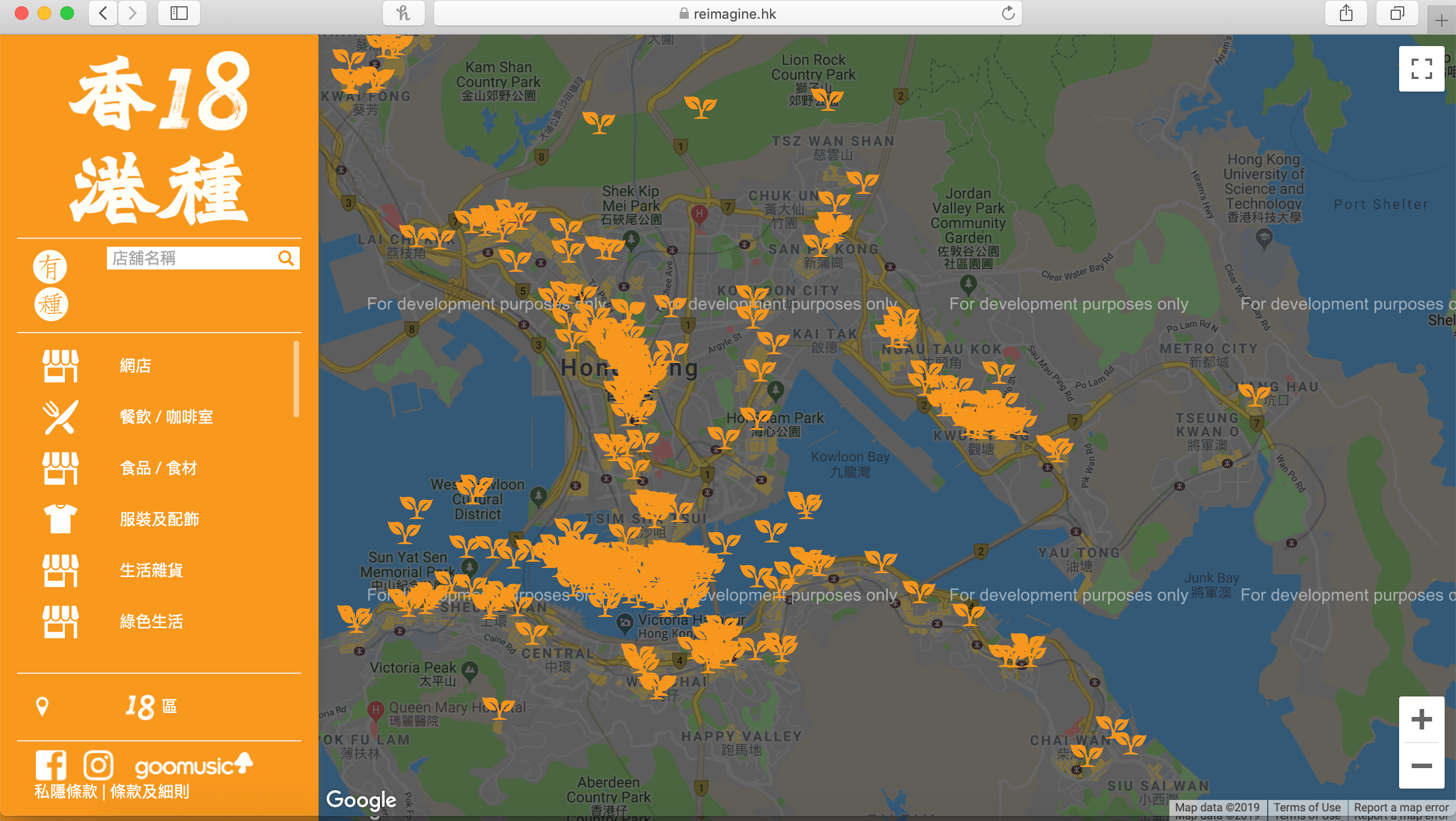

The protests have enjoyed extensive societal support. One million marched on June 9, 2 millions on June 16, and 1.7 millions on August 18. Many professional groups have organized protests one after another: medical staff, social workers, journalists, civil servants, lawyers, airlines crew, teachers, accountants, surveyors, architects, financial sector staff, and many more.

The police cannot lock up every dissenting voice. But Beijing has dramatically raised the costsof supporting the protests.

- For Cathay Pacific Airways, Beijing has forced it to choosebetween its China business and its employees right to protest, banning crew member who had. The pressure has led to the resignation of the CEO and the sacking of pilots and ground staff.

- The big four accounting firms in Hong Kong are also pressed to identify employees who placed an advertisementin the pro-democracy Apple Daily.

- Teachersare targeted by China’s People Dailyfor polluting young minds.

- TVB, HK’s main TV station, has fired over 20 staff for pro-protest comments.

The extent of Beijing’s erosion of HK’s autonomy is nicely captured by one social media meme: HK’s police, airlines, and television stations no longer belong to Hong Kong people, because the Hong Kong government does not belong to Hong Kong people.

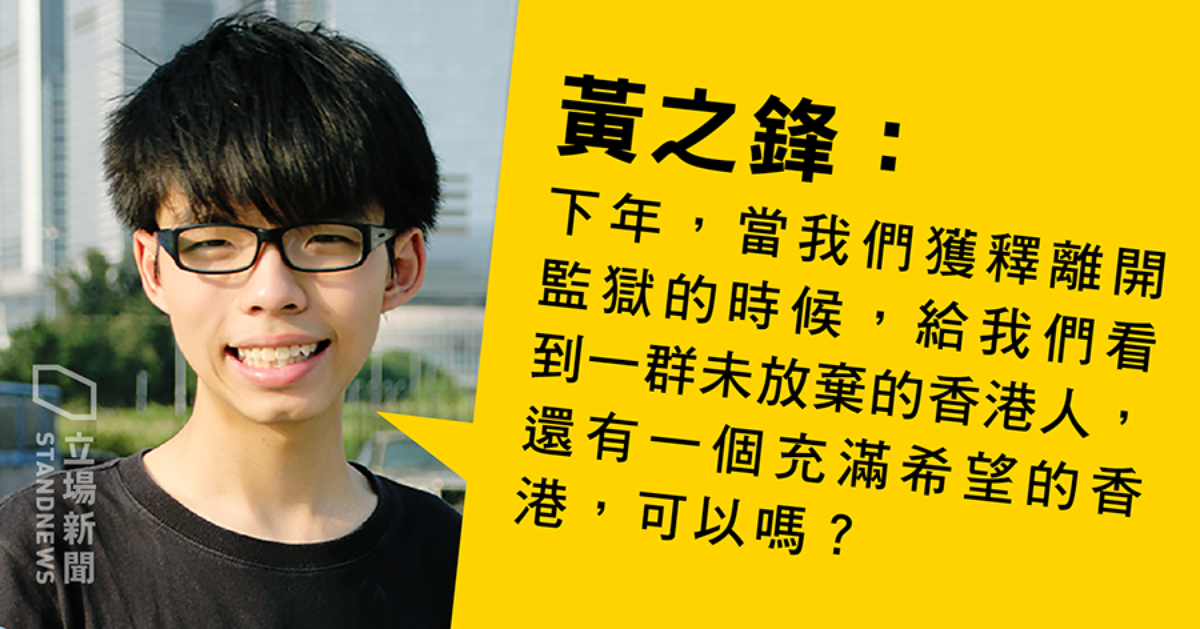

Hong Kong’s Last Stand

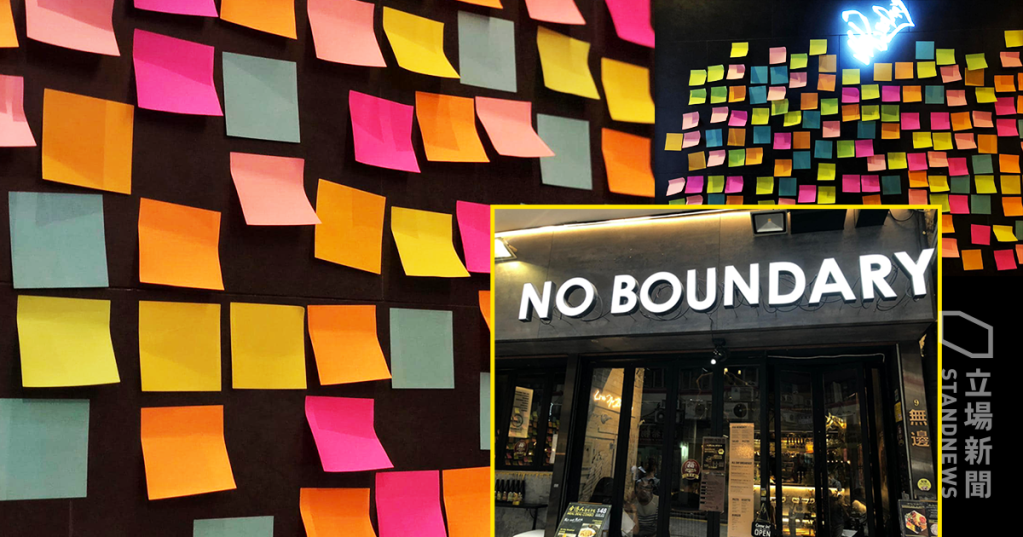

Yet, the combination of bloody crackdown and white terror has only stiffened Hong Kong people’s resolve to defend the freedoms that they have grown up with.

They see this struggle as the “last stand” because they are fast losing even the basic freedom – the freedom from the fear of getting beaten by police officers and gangsters, and the fear of getting fired for simply saying “Go, Hongkongers (香港人加油)!”

Stand with Hong Kong

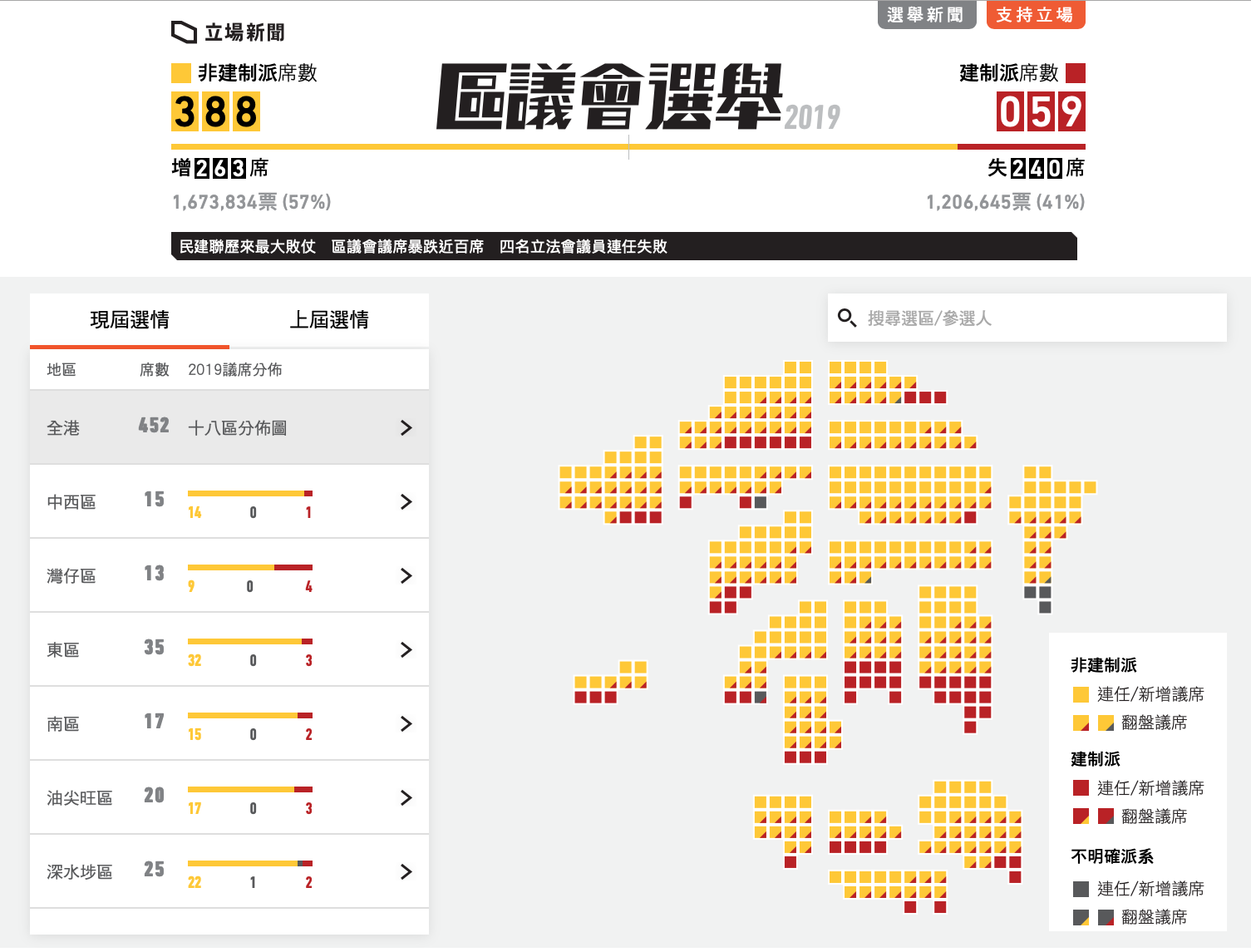

We don’t know how the protests will unfold. What the determined Hong Kong people have achieved so far is to fully expose the lie that Beijing has kept its promises to Hong Kong.

If there is anything left to “one country, two systems,” it is the people of Hong Kong themselves – it is their will to keep defending their freedoms at huge personal costs.

The world’s democracies should stand with them. Hong Kong protesters have called on the US Congress to pass the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act. Protestors have called for international condemnation of police abuses, and for closer monitoring of the less visible white terror. Hong Kong people have called for closer international monitoring of the right to protest – they should not have their heads and limps broken under arrest. Hong Kong women have called for protection of their dignity – they should not be subject to strip search and sexual assault by the police. Hong Kong’s medical staff have called for international humanitarian assistance. They should not be denied access to injured and they should not themselves be arrested. Hong Kong’s social workers have called for attention to similar humanitarian concerns. They should not be arrested for providing social service to protestors.

Stand with Hong Kong!

Thank you.

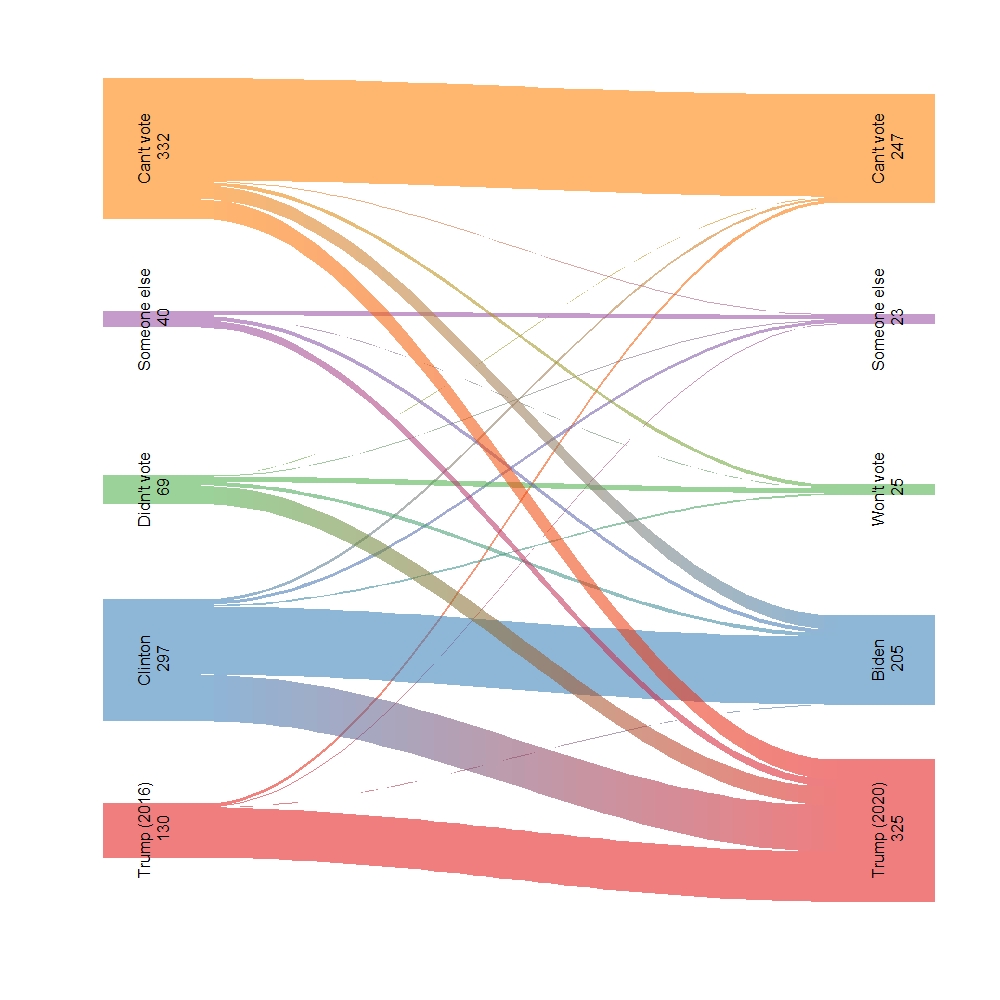

Figure 1: Vote change in presidential candidates (2016 and 2020).

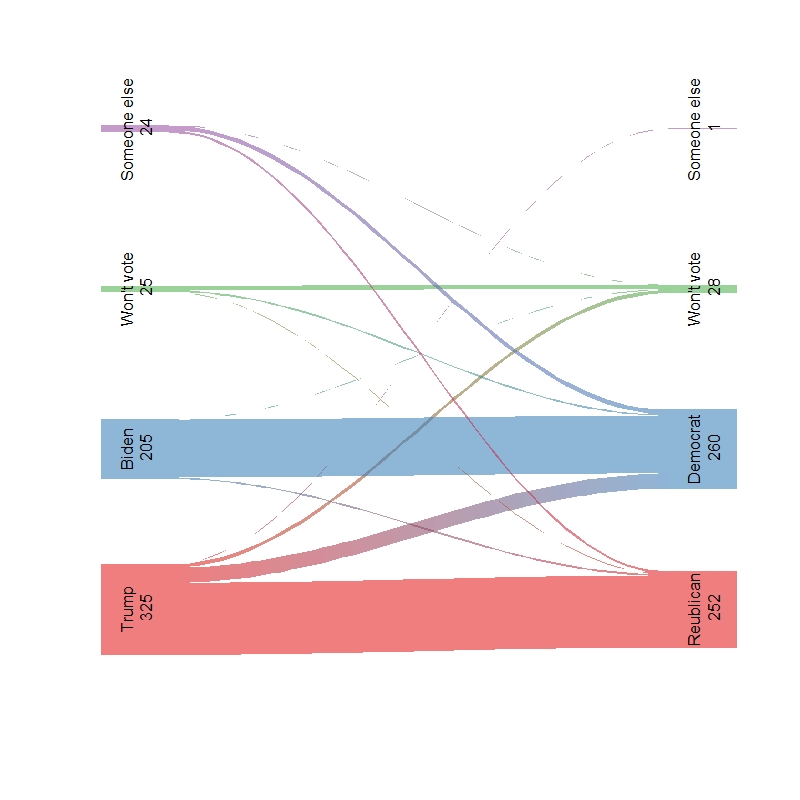

Figure 1: Vote change in presidential candidates (2016 and 2020). Figure 2: Split-ticket voting in Presidential and Congressional elections in 2020.

Figure 2: Split-ticket voting in Presidential and Congressional elections in 2020.

[

[